Why Is Remote Learning So Hard? (Full Article)

By guest author: Peg Dawson, Ed.D., NCSP

Why Is Remote Learning So Hard?

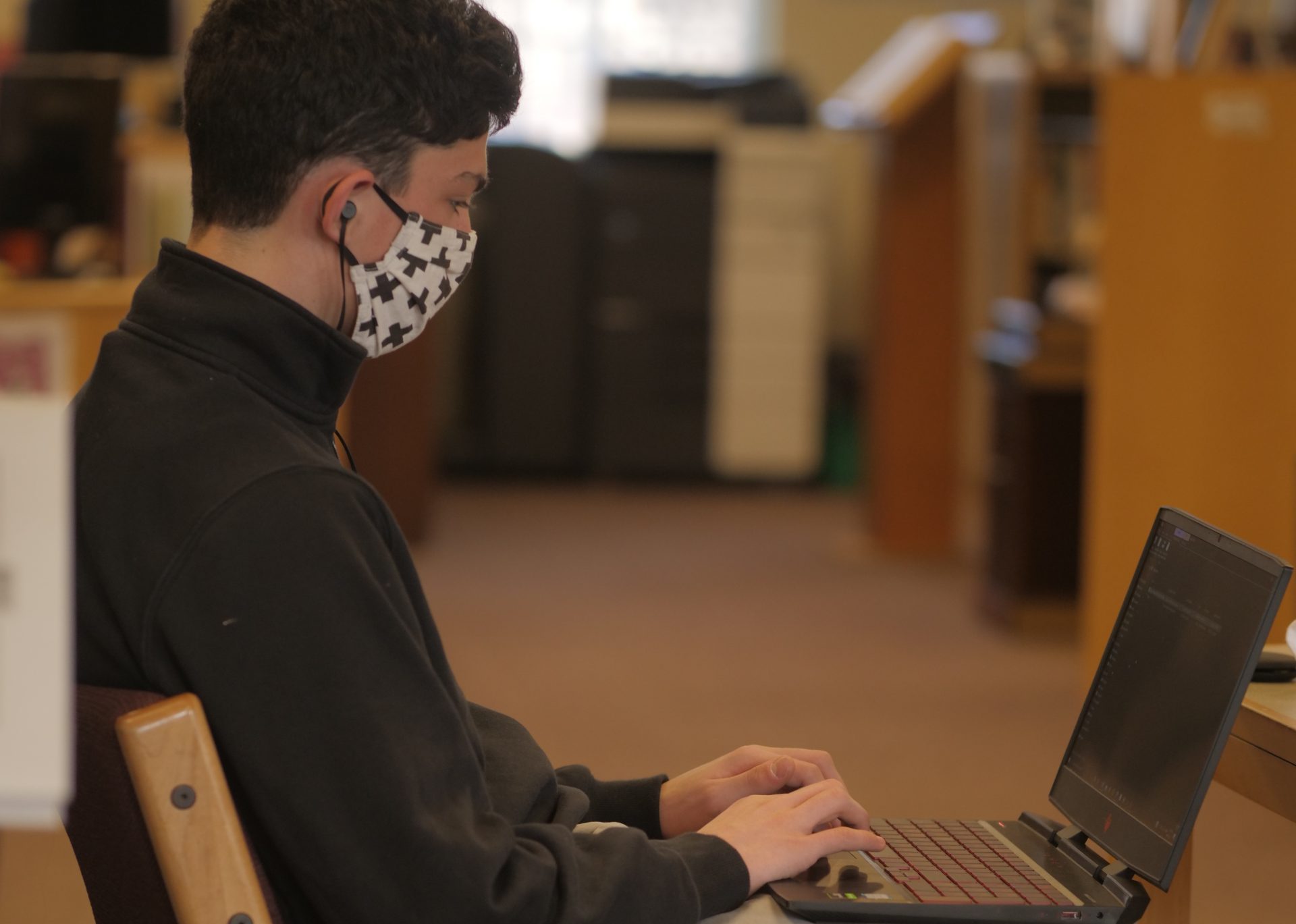

For many years, I’ve been leading a study group on executive skills sponsored by the New Hampshire Association of School Psychologists. When the pandemic hit last March, we switched from meeting in person to meeting over Zoom, and it’s given me the opportunity to observe how distance learning has impacted student learning and performance in schools in my state. Because my area of interest and expertise is executive skills, I’d like to look at the effects of the pandemic through that lens.

At our latest study group meeting, we spent a fair amount of time talking about how different schools are structuring instruction. Most schools have set up schedules for teachers to follow in terms of when zoom classes are scheduled and how long each class lasts. In most schools, it appears that teachers are given a lot of leeway in terms of how they actually structure instruction, although at least one high school that uses block scheduling breaks down 80-minute classes in a 20-40-20 format with teacher-led instruction for the first and last segments and interactive or individual activity in the middle segment.

It appears that distance learning is going a little better at the elementary level than at the middle/high school level. At two high schools, school psychologists estimated that about half the student body are currently earning D’s and F’s.

In my mind, I keep going back to what changed when in-class instruction was curtailed. I’ve maintained that what got exposed was what I call the “hidden curriculum.” People expect kids to have executive skills but no one’s charged with teaching them. And for learning to take place, students either have to have very well-developed executive skills (which may not be developmentally appropriate, since these skills take a minimum of 25 years to reach maturation), or sufficient external supports need to be provided so that weak executive skills don’t prevent kids from learning.

It appears that distance learning is going a little better at the elementary level than at the middle/high school level. At two high schools, school psychologists estimated that about half the student body are currently earning D’s and F’s.

A quick definition of executive skills: these are a set of behaviors, managed out of the frontal lobes, that allow students to “execute tasks”—or in the words of a second grade teacher I know who wanted to figure out how to explain executive skills to children in her class, they are the skills you need to get things done. In the model that my colleague, Richard Guare, and I developed, the executive skills we feel are the most critical to school success are: response inhibition, working memory, emotional control, flexibility, sustained attention, task initiation, planning/prioritizing, organization, time management, goal-directed persistence, and metacognition.

So what external supports do schools, classrooms, and teachers typically provide with in-person learning that enable children with under-developed executive skills to be successful? Here’s a short list:

- An externally imposed schedule.

- Continuity—the schedule stays pretty much the same on a daily or weekly basis, so that students know what to expect on any given day in any given class.

- A location where learning and teaching are the sanctioned activities.

- A set of learning activities with externally imposed start and stop times.

- Visual cues to help students understand instructions and stay on task.

- Immediate support for students who struggle with the learning tasks.

- Common organizational structures (classrooms and desks) where learning materials are kept and made readily available.

- Limited expectations for students to manage their own time. By this I mean homework assignments. With in-person learning, homework is limited to more proscribed work and the expectation is that most of that work can be done fairly quickly and handed in the next day. With distance/hybrid learning, students have much greater blocks of time to manage on their own and are more likely to have assignments that are spread out over several days (especially if their classes don’t meet every day). Even before the pandemic, block scheduling and long-term assignments posed a challenge for students who struggled with time management and planning. With distance learning, the problem is worse.

- The presence of a peer group that reinforces focus during in-class instruction and work completion. Peer groups also meet the social needs of students so that during non-instructional times, friendships are made and strengthened. For some kids, getting to see their friends in school is the primary motivator to get them out the door in the morning.

- The emotional connection between teacher and student. For some kids, the emotional connection they have with their teachers is what propelled them to do work they didn’t find particularly interesting or appealing (or at least less interesting or appealing than the other ways they spent their spare time). That emotional connection becomes much more tenuous when the only contact a student has with a teacher is through a Zoom class, with little opportunity for private conversations and words of encouragement.

When you peel all that away, what’s left? You’ve basically taken away massive amounts of support for executive skills. In the absence of all that scaffolding, the student basically has to impose self-discipline. When one googles this word, here are some of the definitions that come up:

- Self-discipline is the ability you have to control and motivate yourself, stay on track and do what is right.

- the ability to make yourself do things you know you should do even when you do not want to.

- The ability to make yourself do the things you know you ought to do, without someone making you do them.

One of the sites I looked at noted that “Self-discipline is typically a learned behavior that people refine over time through practice and repetition.”

So basically, the pandemic took away all the supports that kids (and their parents) typically rely on for school performance and expected students to develop self-discipline with none of the practice and repetition that allows that skill to be developed!

Translating “self-discipline” into executive skill terminology, we’re basically talking about response inhibition, task initiation, and sustained attention. It’s the ability to set aside fun stuff or preferred activities, to start non-preferred activities (such as class attendance and homework) and to persist with them until the activities are completed. And to be able to propel oneself to do that all on one’s own!

When I asked people in the study group what was the biggest issue they saw that was making school so challenging this year, the answer was “lack of engagement.” Engagement is less of an issue when all the external supports provided by in-person learning are present. Take away the supports and students “have to want to do it.” Or “have to make themselves do it”—and now we’re back to self-discipline.

When I asked people in the study group what was the biggest issue they saw that was making school so challenging this year, the answer was “lack of engagement.”

I think the challenge is to find ways to reproduce the external supports that in-person learning provides. For the “disengaged” students, it has to begin with helping those students make the social connections that have been severed: either more contact with their peers or a stronger personal connection with a teacher or another caring adult at school—or both.

Once we’ve strengthened those social connections, then we have to help them figure out how to structure their time more effectively, which brings us back to response inhibition, task initiation, and sustained attention.

Felicia Sperry, a school psychologist in the Oyster River School District, shared an activity she did with 4th grade students at the elementary school where she works. At our last Zoom meeting, I shared a Study Plan form that I’d had teachers use effectively for helping students plan their homework time. She adapted it and introduced it to the students at Mast Way Elementary School that she worked with last year using her “Train the Brain” curriculum to teach students about executive skills (and the brain more generally). Here’s the form:

Name: ______________________________________ Date: _____________________

School work planning sheet

| Priority Order you will do it | Assignment What do you need to do? | How long will it take me? | What time will I do it? | Where will I do it? | Actual time Start / Finished | DONE!  | |

My Successes: (what worked for me) ________________________________________________________________________

My Challenges: (what did I struggle with) __________________________________________________________________

Goal for next time (something I’ll keep doing or something I’ll change) _____________________________________________

Felicia reported that she was able to generate really good discussions with students about how they planned their homework and what helped them to get their work done. She commented that she wasn’t sure whether students would use the form to plan on their own, and mentioned that teachers were reluctant to require students to do this. When I thought about this afterwards, I began to question why you wouldn’t make this a required assignment.

Which brings me to the final point I want to make. I think we need to rethink the overall goal of instruction during the pandemic. Rather than focusing on teaching content, I think we need to focus on teaching executive skills. I think we should develop individual learning plans for each student that focuses on helping them develop and strengthen executive skills. Of course, they’ll be applying these skills to subject matter content, but shifting the emphasis from mastering content to mastering executive skills could be profound.

As I envision it, you’d begin by assessing students’ current level of executive skills and then help each student develop a plan that works for them. By collaborating with students on this plan, at a minimum you’re getting them to use goal-directed persistence, time management, planning, and metacognition. And if they come out of the pandemic with those skills strengthened, imagine how quickly they can make up lost ground with content area instruction.

Change at the system’s level is incredibly difficult, so I would be surprised if anyone took me up on this suggestion. But even if this attempt at system’s change is unlikely to happen, please spread the word about the hidden curriculum. We have an amazing opportunity to get people to think differently about how learning happens. Let’s not waste it!

Peg Dawson, Ed.D., NCSP, is a past president of NASP and the co-author of numerous books on executive skills. For several years, she has run a study group on executive skills sponsored by NHASP.